Now at the beginning of July, in a chaotic time of uncertainty, rage and hope, I look back at those first few weeks of lockdown with a mix of wistfulness and incredulity. Still too close to make objective sense of it, yet it already feels distant as many people return to pre-Covid activities. Despite superficial familiarity, there is no doubt that both the atmosphere and physical environment have changed. The restrictions imposed a simplicity to life, which could be relaxing in the moments when I could submit to that. As the environment became busier again, an air of tension built up – there is now a nagging drive to be productive, to return to something, only to find that it is still not possible to make much progress on projects, without difficult adaptations. And there is very little funding available.

What of those weeks, those strange times in which I walked? In the first 2-3 weeks of lockdown in March and early April, I did not go far. Partly out of obedience following Government instructions to stay at home, and partly because I was focused on spending time with family and homeschooling.

In that early stage, my daughter, Eliza and I looked at old maps of Frankwell, the place on our doorstep, and we researched as much as we could find in books and on the internet about our local history as we couldn’t get into the library any more. Then, inspired by Common Ground’s local distinctiveness projects, we created a Frankwell alphabet using images of letters taken from local signage.

A Frankwell alphabet

I began to think about whether I could create an A to Z Book of Frankwell with drawings of places for each letter. These are some of the drawings in ink made from oak galls from the tree in our garden. Some of the drawings refer to old photographs of places, since demolished.

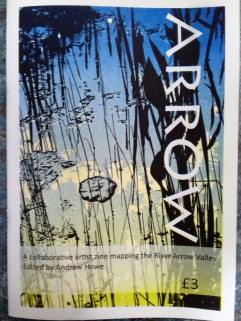

This seed of an idea developed into plans for more artist books to be made in response to my walks during lockdown. At the latest count, I have five of my own books, a collaborative book and two maps on the go. These comprise a set of black and white prints exploring distinctive lines and patterns found in Frankwell, and two series of photographs inspired by some of Robert Rauschenberg’s image sequences and screenprints. I got in contact with some of the artists I know living in or connected with Frankwell and we developed an idea to create a collaborative book which could help rejuvenate community interest and, perhaps, raise some money for charity. I’ll post about these books as I/we complete them.

Linocut and relief test prints of structures, lines and patterns distinctive to Frankwell

When I did walk it was usually early in the morning when very few people were around. Those weeks of Spring will be remembered for seemingly endless days of perfectly warm sunshine and crystal clear blue skies, not an aircraft trail in sight. Few people failed to notice the Spring this year, as so much time could be spent outdoors, listening to bird song and watching the emergence of seedlings and flowers. Through regular walks, it was possible to pinpoint the day swifts arrived, or when hawthorn came into flower.

In about the fourth week, I began to record my walks a little more formally beyond taking photographs to making notes of observations and experiences.

Inspection cover cast at the Atlas Foundry, originally located in Frankwell, where Theatre Severn now stands

I collected wax crayon rubbings of surfaces, and occasionally some found artefacts, like fragments of pottery I found in the River Severn both upstream and downstream of the town. Someone later advised that some of the fragments were likely 17th or 18th Century slipware. Other pieces, like the earthenware fragments, looked like they could be even older. Each fragment must have its own story. It was fascinating to think of the journey of the clay, from its formation thousands, if not millions of years ago, to its extraction, processing and making into utensils which were somehow lost and broken, transported and eroded in the river to be collected once again from the shore.

Ceramic fragments collected from the River Severn

The government had tried to clarify guidance about where and when people could exercise. There wasn’t any definitive distance set, but at that stage, we were not supposed to drive anywhere to walk. So, I restricted my walks to within a 2km radius of my house, and I also restricted myself to not walking everyday. The imposed conditions increased my anticipation of each walk, and exploring within the local boundary became a highlight of the week.

Ordinarily, I don’t use an automated GPS tracking of my walks, preferring instead the ritual of tracing the route on a map after the event, which helps to fix the walk in my memory. Seeing the shape of the routes, set against mapped topography gave the walks a tangible presence linked to sensory encounters.

Weekly mapping of walks

A walking web of routes with 15 minute and 30 minute radial points to be connected by walking as close to a straight line as possible

Having lived in Frankwell for over 22 years, there are few if any places I haven’t walked in before, but the heightened awareness, the disrupted sense of time and space, meant that I did see details with fresh eyes. The urban environment is a gallery of contemporary art.

As I went slightly further afield beyond Frankwell, I did occasionally find a new pathway or a road that I had never previously visited. I was conscious that I might be viewed as an intruder, as being a potential asymptomatic virus threat, in the quiet residential streets. What was the purpose of my walks? Was I staking some kind of psychological claim over territory, was I the self-indulgent flâneur, was it just exercise? I don’t think it was any of these particularly, although it was certainly as much a mental exercise as physical, a chance to let my mind breathe in the open air and escape the confines of domesticity. I was curious to experience directly how the world was reacting to this new situation, to record and reflect on how we can find positive routes out of this.

That said, I couldn’t help feeling pangs of selfishness when hearing about or seeing for myself how people were discovering local paths that were completely new to them, paths I had walked many times, talked about, made artwork about, and which had generally been met with disinterest. Rightly or wrongly, these are places where I felt some kind of ownership. Really though, it was great that there was a surge of interest in our surroundings and slowing down, which offers renewed optimism about future attitudes. It is what this blog and much of my artist practice is about encouraging after all.

Against all this familiarity, I was noticing the differences – changes in the natural and built environment, and changes in people’s behaviour. Children were making the best of the sunny weather and chalked pavement drawings and upbeat, hopeful messages were much in evidence. Trees became decorated with bunting, ribbons and curious paraphernalia, boxes and piles of junk appeared at the end of driveways as people found time to sort out their house. Desire paths were worn across verges and patches of grass, sometimes a parallel line appeared 2m from the main path.

As the weeks passed, the choreography of encounters with other pedestrians evolved. After the initial awkwardness of crossing the road or stopping and standing well aside to avoid passing close to someone walking in the opposite direction, there was a period in which there was the briefest of eye contact, smiles and gracious thank yous and careful, elegant swerves to maintain 2 metres’ separation. These actions became more unconscious then from around the ninth week, it was noticeable that a small number of people were not only intent on ignoring social distancing, there was an element of aggression in the way they steadfastly maintained a line along the middle of the footpath.

Once it was announced that lockdown restrictions would be eased and some non-keyworker school children would be able to return to school, I detected a renewed sense of purpose in the people I saw during my walks, traffic had been getting busier again, and my walks began to lose their charm. I stopped recording the walks after Week 10, a suitably round number, and suddenly my interest waned. The sense of community cohesion that had grown during the lockdown began to dissipate, but there continues to be many voices calling for a more sustainable recovery and hope remains that whatever world we return to, it will shed some of the old baggage and head in a socially just direction.

Tags: Covid Walks, Frankwell, Mapping, the lure of the local, walking, walking artist